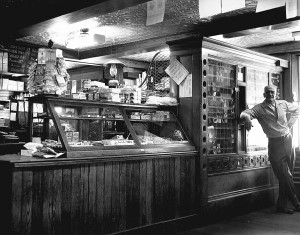

Princeton once enjoyed a group of sages called the Pot-Bellied-Stove Philosophers. They met in D.H. Gregory & Company’s store (2 Mountain Rd.) and gathered (as the name implies) around the pot-bellied-stove with its accompanying box of sawdust to discuss the affairs of the universe.

Not all of them made use of this latter receptacle, although as long as J.D. Gregory managed the affair, indeed as long as he lived, only plug tobacco was sold, and that was kept out of sight under the counter. As a child this writer, on the few occasions when she witnessed the cutting off of the savory-smelling plugs, used to reflect that if tobacco tasted as good as it smelled, the chewing habit might be worth exploring.

Not all of them made use of this latter receptacle, although as long as J.D. Gregory managed the affair, indeed as long as he lived, only plug tobacco was sold, and that was kept out of sight under the counter. As a child this writer, on the few occasions when she witnessed the cutting off of the savory-smelling plugs, used to reflect that if tobacco tasted as good as it smelled, the chewing habit might be worth exploring.

The aforesaid stove appeared from its summer resting place along on the Fall when it became necessary to warm the store, and was set up nearly in the geographical center of the room. Its funnel rose to the ceiling, then by means of an elbow was directed toward the wall behind the counter, thence along the ceiling fifteen or twenty feet over the dry-goods section into the chimney. This expanse of pipe furnished considerable heat.

Around the stove were straight-backed chairs which, during cold winter days especially if stormy, were almost always occupied by some of the middle-aged and older men of the community, chewing, expectorating, and arguing. Each newcomer revived the dying out of some nearly-exhausted subject. Although themes of tariffs and free trade were never settled, still the subjects were so thoroughly dissected and chewed over and spit out that actual knowledge of the controversial points at issue finally came to the surface.

Wilkes Davies

One of the outstanding characters of the sage circle was Wilkes Davis, a typical Yankee, rather above medium height, somewhat bleary-eyed, with tousled hair gathered in under a worn black hat, which it would not have occurred to him to remove even if Madam Boylston herself were to enter the store. His once stalwart frame showed unmistakable signs of hard-work wear. His well-considered language expressed with unusual acuity and clarity of thought developed the public idea that he would have made an excellent lawyer.

But he was a stone mason by trade. He could select a huge boulder or well-exposed out-crop of granite and drilling by hand shallow holes six or eight inches apart, and driving wedges he could split off pieces of stone according to any prescribed specifications.

His handicraft can still be observed about Princeton. The best monument to his skills stands over the grave of his wife, the obelisk beautifully smoothed by his tough-skinned hands, but not polished.

Wilkes was not exactly cantankerous, but he usually took the opposite side of an argument, defending it strongly and so persuasively that the group as a rule was won over to his side; then another member of the circle would appear, bring up the same subject advocating the very point just agreed upon. After the new-comer had clearly declared his position, Wilkes would at once question the plausibility of his reasoning and with quiet vehemence attach successfully the facts already agreed upon; thus championing both sides victoriously.

Dr. Oscar Howe

Another member of the pot-bellied-stove circle at the village store we reported about in an earlier article was Dr. Oscar Howe, the town dentist, grandfather of Mrs. Harry Donnelly. He lived on Gregory Hill not far from the store and had his office in a small building across the driveway from his home. Some of his tools are on display in the PHS Museum Room at the Princeton Community Center.

His appearance resembled Robert Browning Esque, short, rotund, with a little white beard. When he smiled, perfect dentures probably of his own making were disclosed, one incisor bearing a neat gold filling. (This writer spent some time conjecturing why the gold filling in “store teeth”, or in case the teeth were natural, how he managed to put in that filling himself.) A cause of deep envy was the fact that Dr. Howe never had to wait in line to have his mail handed to him, but produced on a chain a little key which admitted him at will to one of the choice closed-in P.O. boxes.

Dr. Howe was a good dentist. His reputation drew him to Westminster one or two days a week and persons with ailing teeth came to him from surrounding towns. It is not too much to say that he was years ahead of his time in the art of making lifelike dentures. The only professional contact this writer ever had with him was once when I was sent to his office to procure some tooth powder. Fascinated, I watched him mix enough red substance into white powder to produce a beautiful pink, the powder being flavored with checkerberry.

To continue in Dr. Skinner’s words: “Dr. Howe was one of the very first in rural sections to employ an anesthetic for extractions. He used “laughing gas”, making it himself. Once I stepped into his office when he was at work. He placed the chemicals in a retort, heating them over a kerosene flame, conducted the gas through a purifying chemical. A short distance further the gas bubbled through chloroform. The tube then entered a gasometer standing in one corner of the room. From the top of the receptacle protruded a cloth-covered tube quite large in my estimation. It extended to the ceiling, then ran toward the operating chair, being held up in graceful loops by wire brackets hanging from the ceiling and finally ending in a face gas-mask. This hung like a nemesis over any and all patients who had to sit in the chair to receive the painful ministrations of the dentist.”

When extractions were imminent, the string holding the mask up was released, and the mask was closed tight over the victim’s face. No oxygen was used and no air allowed entrance. After the first five whiffs, or what is worse ‘deep breaths’, the patient would feel his chair tip over backwards, and through the murky gloom would hear the funereal voice: ‘Wake up! Wake up! The tooth is out.’ Why the good doctor didn’t kill anybody was, and still is, a mystery to me, for that concoction was deadly.”

Mrs. Donley has in her possession papers which show that April 7, 1863, Dr. Howe received $50 for playing the church organ for a year, and $3 for ringing the church bell. At this time the church stood across the street from its present location and the balcony housed the organ and choir.

The case of stuffed birds in the Goodnow Library came from the little doctor’s office.

Ethel Mirick

Updated/Clarified in August 2015 by PHS Board Members.

Note:

- The stuffed birds are now on display at Wachusett Meadow Wildlife Sanctuary.

- Some of Dr. Howe’s dental tools are on display in the Princeton Historical Society Museum Room (18 Boylston).